This post will focus on an eighteenth century building which is again situated in the heart of the Northern Quarter and just around the corner from my previous post on Kelvin Street.

Number 2 Union Street has had long and varied life, for about 130 years it was known as the Bulls Head Inn (later Hotel) and its later uses reflected the changing nature of the Northern Quarter and the city as whole. This building is also currently earmarked to be part of a major development plan in the Northern Quarter.

A Historical Puzzle

Number 2 Union Street has a confusing history. Union Street itself is a side street which connects Turner Street and Church Street. It is located towards the Shudehill end of the Northern Quarter. The street would have been laid out in the mid-eighteenth century, it appears on Tinker’s map of Manchester dating from 1772.

The building is suitably grand and impressive, even today in its run down state. Historians and architects studying the Northern Quarter have been puzzled by this imposing building, which is tucked down a relatively insignificant side street. It is clearly Georgian in design but much larger than surviving buildings of a similar age. Some have speculated this was originally designed to be a domestic dwelling, which later became a pub. It is easy to imagine the architecture of this building in the more affluent areas of Georgian Manchester, such as King Street or St. John Street.

I have used the Rate Payer’s Books, located at Archives +, to try and solve the mystery. The books are a brilliant resource and cover most years but not all. I started in 1795 which assessed the value of the houses on Union Street as being worth about £3. Therefore, none match the description of our building as its size means it would be worth a considerably higher figure. The subsequent rate books of 1796, 1798 and 1802, once more list houses of low values (even unoccupied properties). Furthermore, none are described as a public house and no new buildings were constructed. This is evident from the pattern of householders, which remains the same for the period covered: Margaret Wilson, John Cherlot, William Holland, James Pint and James Tilford.

However, in 1804 a new building appeared on the street, a public house valued at an impressive £25. Moreover it is located at Number 19, next door to James Tilford and at the end of our pattern of neighbours. This is the modern day Number 2 Union Street. Therefore, the Rate Payer’s books infer the building was a purpose-built public house, constructed between 1802-1804. Although, it could also be that the building was designed as a house but very quickly became a pub. The absence of any building being recorded, either occupied or unoccupied, between 1795-1802 suggests that the new building did not replace an earlier house or pub.

The Architecture of 2 Union Street

Number 2 is an impressive building and it was owned by, and presumably built by the Welch family. It is brick-built with a Flemish Bond design façade and features four-stories (including cellar) and three bays, with a grand front entrance. The windows on the front of the property have been altered over time, although they exist in their original formation of two at ground floor level, three at first floor level and three at the second floor level (one window on this level is the best preserved example of how it would have looked when built.) The round headed window on the left hand side at first floor level is not mirrored on the right. This is because the right hand window was altered in the twentieth century to created a high level passage-way which once linked 2 Union Street with 25 Union Street across the way. The right hand window on the second floor has the remains of warehouse doors inside, which is reflective of the change of use of the building over time. A small doorway on the left of the building enabled access to a rear courtyard.

The rear of the building is built in an English Bond brick, it is quite common to find late eighteenth and early nineteenth century properties with different bonds of brickwork, with the more decorative pattern being used on the front. A large additional wing projects from the rear of the property, with warehouse doors at the second floor level (which mirror the ones that would have existed on the front). There are also examples of two sixteen-pane sash windows and two eight-pane sash windows (all in very poor condition) but the size of these rear windows again reflect the prominence of this building, as the window tax was still a prevalent part of life in Britain until 1851 when it was abolished.

The interior of the building is in a very dilapidated state, with the collapse of some of the internal ceilings. The only original features to survive are the Georgian spindled staircase (in a poor condition), the stone steps down to the cellar and some examples of lathe and plaster ceilings.

Early Nineteenth Century Developments

By 1805, just after the Bulls Head was built, Union Street had already fell into decline and was no longer a desirable residential location. For example, an advertisement concerning the sale of two houses that year states they could be easily converted into warehouses for “trifling expense”. There was also a large factory on the street belonging to a Mr Knight, containing a 40 inch double engine carding machine, an early example of industrialisation in the city. The expansion of this area is reflected in the address of the Bulls Head, as the door number changes as more domestic properties on the street were demolished and replaced:

- 1804 = 19 Union Street (Rate Payer’s Book)

- 1828 = 17 Union Street (Pigot’s Trade Directory)

- 1841 = 12 Union Street (Rate Payer’s Book – this is the first time the street has been split into an even and odd side, before that the houses were listed consecutively)

- 1868 = 4 Union Street (Rate Payers Book)

- 1871 onward = 2 Union Street (census)

The first landlord of the Bulls Head Inn was Abraham Leech, who only stayed around a year or two. He was followed by Charles Woodwise in 1806 and John Beaumount in 1807 (by this point the assessed value of the property had doubled to £50).

John Dean was landlord at the Bulls Head from 1812 until his death c.1819 and was succeeded by his wife Charlotte (1786-1854). John had married Charlotte Hartley in 1805, when she was 19 years old. They had four children together; Margaret (b.1806), John (b.1808), Peter (b.1811) and Charlotte (b.1813). After John’s death, Charlotte ran the pub as well as raising her family for a couple of years until 1822 when she married John Manning at Manchester Collegiate Church (now Manchester Cathedral). In compliance with British law at the time, everything Charlotte owned passed to her husband upon their marriage. Therefore, John Manning was listed as landlord of the Bulls Head until his death in 1832. Once again Charlotte was widowed and she quickly had to adapt again to continue running the pub alongside raising three more young children from her second marriage; John Dean Manning (b.1823), Richard Manning (b.1826) and Thomas Manning (b.1828).

The 1841 census recorded Charlotte and her youngest two sons as the Bulls Head Inn along with two servants; Mary Sinclair (b.1789) and Margaret Powell (b.1826). Also recorded are John and Bridget Bradbury and James Harrison, possibly lodging for the night at the time of the census. Charlotte and her family left the Bulls Head in the early 1840s and moved to Johnson Street, Cheetham, a suburb of Manchester. Charlotte lived there until her death at the age of 68 in September 1854.

The Mid-Nineteenth Century

The next few years marked a quick succession of landlords and landladies at the Bulls Head; John Pownell (1845), William Nicholson (1846), John Youil (1847), Anne Wetherall (1847), Thomas Cox (1849), Thomas Brumfitt (1849-51), James & Nancy Fields (1851-54), John Hartshorn (1854), Harriet Bradley (1855-58) and Thomas Matthews (1862).

In February 1849, in between the tenure of Thomas Cox and Thomas Brumfitt, the fixtures and fittings of the Bulls Head were auctioned off. The newspaper article provides us with an idea of how the pub would have looked in the mid-nineteenth century:

“On Friday next, the 9th of February, 1849, at the Bull’s Head Inn, Union-street, Church-street, Manchester; sale to commence at eleven o’clock in the forenoon:

THE very Useful FURNITURE and FIXTURES of this establishment, comprising substantial chairs, mahogany and deal dining, card, bar and coffee-room tables, glazed bookcase, musical clock, capital 8 days spring timepiece by Walmsley, black leather and carpet covered hair seating, painted and gilt ornamental spirit casks, twelve-tap spirit fountain, five-tap ale and porter fountain, glasses, earthenware, fenders and fire-irons, oil cloths, carpets, mahogany, birch and painted four-post, tent, and French bedsteads; mahogany chest of drawers, bureau, washstands, dressing tables, toilette glasses, bedside carpets, feather and flock beds, bed linen, blankets and counterpanes, together with the glazed doors, partitions, gas fittings and other effects.”

Late Nineteenth Century

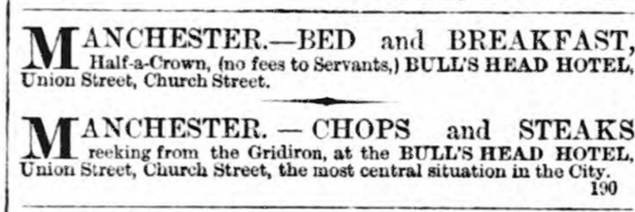

From 1857 the business had reinvented itself as the Bulls Head Hotel, which gave it a more refined status in inner-city Manchester. Bed and Breakfast was offered for half a crown, with no extra fee for servants (£10.75 in modern terms). In 1868 James Lodge became landlord, but just a year later the building, and adjacent plots of land were sold by Messrs. Daniel Bradshaw & Son & Balshaw. Whoever purchased the building kept James Lodge as landlord as he was still recorded there in the 1871 census, along with his wife Elizabeth, step-son John Thorpe, sons; James and Frederick and two servants and a visitor.

By 1872 the Bulls Head Hotel appeared in the press as the Bulls Head Hotel & Restaurant. A newspaper advert reveals they still offered lunches of chops and steaks from 12:30-2:30pm. The offering of hearty meat dishes reveals the dining room was aimed at men who worked nearby in the city centre and desired to socialise whilst they ate. The Bulls Head Hotel certainly would not have been a place where middle-class ladies, who happened to be shopping on Oldham Street, would take refreshments. By the end of the decade, James and Elizabeth Coupe had taken over the business. Meanwhile the owner of the building changed from John Grantham to Robert Waterhouse.

The 1881 census revealed that, just like events 60 years earlier, Elizabeth Coupe had been widowed and was running the business with the help of her children; Elizabeth (aged 24), Mary (aged 23), Jane (aged 20) and William (aged 15), all worked behind the bar. Elizabeth’s other children; James (aged 27) was a silk salesman and Joseph and Edith (aged 13 &12) were both still at school. Also living at the Bulls Head Hotel was Elizabeth’s sister-in-law and nephew, two servants and two visitors were recorded on the night of the census. Sadly Elizabeth died aged 55 only two years after the census was taken.

By the mid-1880s the buildings of Union Street consisted of the pub and warehouses. Numbers 4-6 at the side of the pub is an example of an impressive late nineteenth century warehouse. From 1885-1888 the pub was run by William Donnelly. Following him was Henry Austie along with his wife Amelia and their two infant children. In 1891 they employed a cook, two domestic maids and a boot boy to cater for the guests of the hotel.

In the 1890s there was another quick succession of landlords; George Sawyer (1893-95), Harry Hill (1895-96), James Parker (1896-97) and James Challoner (1897-1900). In 1900 Irish-born couple Francis and Sarah Earley took over the Bulls Head. The 1901 census revealed the Bulls Head Hotel was now surrounded by public houses on most immediate streets. There was the Church Inn on Red Lion Street, Old Wheatsheaf Hotel on High Street, the Unicorn Inn and Spread Eagle Hotel on Church Street, the Barley Mow and Blue Bell Hotel on Turner Street and the Globe on Birchin Lane. Although the substantial size of the Bulls Head was still reflected in the 1911 census (still occupied by Francis Earley) and it was recorded as having 13 rooms.

It was probably in one of these large meeting rooms that the Freemasons, the Garrick Lodge (097) of the Grand Lodge of England would meet. There have been links made with the Bulls Head and the Masons before, in the late eighteenth century. However, further analysis of the 1794 Trade Directory reveals these eighteenth-century links in fact refer to the Bulls Head Inn at Market Place (where Marks & Spencer’s now stands) not Number 2 Union Street. In 1902 the Garrick Lodge sent a telegram to King Edward VII, congratulating him on ending the Boer War.

Twentieth Century: Decline

Number 2 Union Street was still functioning at the Bulls Head Hotel in the 1930s. In 1939 they advertised in the Manchester Evening News for a pianist to play on Friday and Saturday nights, which suggests it was still a popular local venue.

In the Post-War period, Number 2 Union Street ceased to exist as a public house. As early as 1895 J. &N. Phillips & Co., who owned warehouses on Church Street had attempted to purchase the building. By the 1920s the result was letting the upper floors out to be used as warehouses, whilst the ground floor was still a pub. Goad’s Fire Insurance Map of 1926 shows an extension at the rear of the property leading into Bartho, Taylor and Ogden’s millinery warehouse on Red Lion Street. By 1940 there was also a high level bridge from the front window of the Bulls Head linking it to other buildings across the way. In 1956 J. & N. Phillips & Co. finally purchased Number 2 Union Street to use as a warehouse. It cost them £3000 (£63,620 in modern terms).

The ground floor of Number 2 Union Street was latterly used as a cafe servicing the warehouse above. Although a photograph dating from August 1971, located in the Archives+ collection, shows the building with “The Brown Bull” across the facade. So perhaps, even briefly, the building was used a public house again in the late twentieth century.

By 1996 the building was abandoned and it had fallen into disrepair. A request to demolish the building was refused in 1997, as fortunately Union Street falls under Manchester City Council’s Smithfield Conservation Area, which was established in 1987.

2 Union Street Today

Today the building still sits in dilapidated state, as the most recent photographs I have taken of it show. The adjoining former warehouse, and the Northern Quarter as a whole have been smartly refurbished and restored. Number 2 Union Street and the empty land behind it on Red Lion Street are currently earmarked for development into residential properties.

The plans are to demolish the existing structure and start afresh. Luckily the developers plan to preserve the Union Street façade and incorporate this into their design plans (a link is at the bottom of this page). This is a risk which many heritage assets in the United Kingdom face today. Often many fall into such a state of disrepair that it would be more cost effective to knock the building down than to restore it. I suppose a happy medium is to preserve part of the building, the historic front in this case, so that future generations can at least see what was there and how it looked and there is a tangible link to the past. It is clear that some urgent action is need to protect the rest of 2 Union Street before the ravages of time take their toll any further.

Over the past three centuries, the building has been occupied by many different landlords and landladies, and as a public house and later a hotel, it will have felt like a familiar home for generations of Mancunians and those just passing through. Therefore, I suppose it would seem to be a fitting purpose to build new homes behind the historic façade.

Researched and Written by Thomas McGrath

~

Sources:

- Manchester Mercury, 5 February 1805, p.3

- Manchester Mercury, 5 March 1805, p.4

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 7 February 1849, p.1

- Birmingham Journal, 3 January 1857, p.6

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 23 October 1869, p.8

- Manchester Evening News, 29 May 1872, p.4

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 7 June 1902

- Manchester Evening News, 5 January 1939, p.13

- Manchester Evening News, 4 August 1939, p.9

- https://www.hrionline.ac.uk/lane/record.php?ID=871

- http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/d2a1826d-5f8d-4b68-a43d-d92bd2558dec

- https://www.measuringworth.com/m/calculators/ukcompare/

- http://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/511/conservation_areas/1156/smithfield_conservation_area

- http://pa.manchester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?activeTab=summary&keyVal=O33FMYBC6K000

- http://pa.manchester.gov.uk/online-applications/files/4F9673BB003204883FB60666CBA04F8E/pdf/111389_FO_2016_C2-Heritage_Statement_Feb_2016-371850.pdf

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/manchesterarchiveplus/14305641000/in/photolist-nN99EL-8WsSR4-fVPMLD-a5rv3X-ii2dq4-b8rhi8-btuNpa-93AUEL-nN9fxL-nN9ert-fbmEGz-o5kk68-qGFhhG-nF61UJ-dhdAXW-ffMcBg-qGKn1p-dhdyYW-dhdyZV-c13cvL-c13cyh-dhdyQW-dhdz6r-94rR4k-fbmC6c-dRRc7Z-dRWRCo-pKQYjj-aqxAom-dRXr6s-9EwDdm-8WQQZj-dRWLKs-dRRhBc-dRRfc4-dRReua-9wTi6S-dRRpgB-dRRosv-dRRdL2-dRRm5K-dRX1Fu-dRWTY7-dRRjVZ-dhdyFV-dRRj8B-dRWKVb-dRXqfo-dhdypJ-dRRmQR

- http://www.findmypast.co.uk

- http://www.ancestry.co.uk

- http://www.manchester.gov.uk/info/448/archives_and_local_history

What excellent research, I have passed this building many times in the past and knew it was a pub because I found it on the 1915 ordnance survey map.

LikeLiked by 1 person