The only surviving example of what was once a fashionable residential street, today No. 47 Piccadilly looks past its prime. It would be easy to bypass this building and completely overlook it, but it is an important historical landmark in Manchester.

A Brief History of Piccadilly

Piccadilly, the area in Manchester at the Eastern-end of Market Street was originally known as “Daub Holes” in the eighteenth century. The term daub comes from the clay, marle and other materials which were found here and used in the construction of Manchester’s buildings (think of wattle and daub walls). In the sixteenth century, the large pitholes and crevices created by excavations created pools of water and Daub Holes was occasionally used for the punishment of disorderly women who were strapped to the ducking stool and dunked in the water until they were probably half-drowned.

In 1752 Manchester’s Infirmary was founded and the following year land was leased by the Mosley family to construct a purpose-built Infirmary. The building was opened in 1755 and extended in 1756, given the wide-use of the facilities, which only had around eighty beds. In 1794 some 6704 patients were admitted into the Infirmary. The former Daub Holes were themselves replaced by a large ornamental lake.

The site was further expanded in the mid-to-late eighteenth century. In 1765 the Lunatic Hospital was opened in an adjoining building and in 1779 the public baths and wash-house were opened on the edge of the site. In 1790, a non-subscriber to the baths could have a cold bath for 9d.

The area around the Infirmary was known as ‘Levers Row’ in the late-eighteenth century. From 1780, Manchester had its own street named Piccadilly, eventually the name consumed the whole area from about 1812. Piccadilly, took its origins from the name of the street in London, which itself is believed to have been named after the piccadill, a large, stiff lace collar popular in the late sixteenth century and likely produced in that area.

Levers Row

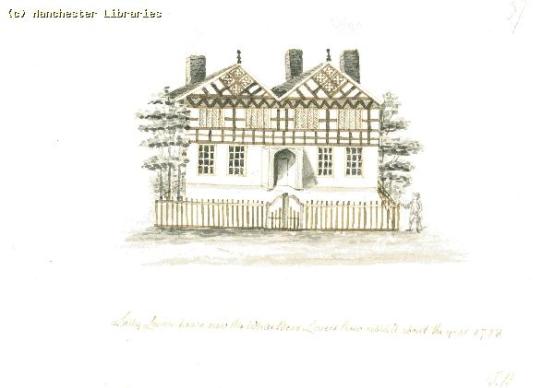

The history of our building starts with Sir Ashton Lever, who gave his name and his land to the housing development located opposite the Infirmary. Lever’s own property, Lever Hall stood just at the top of Market Street (then Market Stead Lane). Lever Hall, also known as Lady Lever’s House, was used by the family as a townhouse. Their modern, country house, Alkrington Hall, in Middleton was designed by Giacomo Lenoni in 1735-6. The much older, timber-framed Lever Hall fell out of favour with the family and in 1771 it was advertised to let: “convenient for an inn, boarding school, or other public purpose; also for any genteel family, tradesman, manufacturer &c.” The fact the possible uses for the once-grand hall starts with an inn, not a house, is telling about the aspirations of Manchester’s population in the 1770s as well as changing tastes in architecture and domesticity. In the end Lever Hall became The White Bear Inn. The original hall was demolished in the nineteenth century and replaced with another public house, itself later demolished. Superdrug now occupies the site.

The houses on Levers Row first appeared around 1776 and their location marked the edge of the town. The residential development proved to be successful, the houses overlooked the large ornamental lake of the Infirmary and they attracted middle-class occupants. The style of architecture at 47 Piccadilly is a reflection of this gentility. The three-bay facade is white stucco on brick. The windows at the first floor level, which would have contained the principle entertaining rooms, have decorative trims and cornices. There is a sill band at the second floor level and decorative dentilled cornice under the eaves of the roof.

The front door would have been on the left-hand side of the ground floor, a door still exists there, and where the shop front is now would have been two windows. The house would have been reached up some stone steps, but the ground floor has been lowered in subsequent centuries. Behind the front door was a hallway, in which a dentilled cornice survives around the ceiling. As was common in eighteenth-century townhouses, the drawing room would have been at first floor level, this allowed the residents a good view out of the window, without being over-looked by pedestrians. In this room, the same dentilled cornice survives which adds to prominence of the first floor. On the second floor, historic architraves and skirting boards survive but are badly rotten.

Who lived there?

I have been able to trace the residents of 47 Piccadilly from 1794 onward. When the property was first built it was known as 21 Levers Row. This later changed in 1812 to 21 Piccadilly and from 1834 the property was known as 47 Piccadilly. The change in door number was a result of other building projects along the same street and the switch away from consecutive door numbering.

In 1794 and 1795, the property was home to Dr John Mitchell. Mitchell was a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society and he acted as the society’s librarian. It was then the home of John and Eliza Cririe from 1796 until c.1807. The street on which the Criries lived was described in 1804 as:

“Perhaps the most pleasant situation absolutely in the town. This arises from its proximity to the Infirmary, which has kept the front free from buildings, and from the gardens belonging to that charity, which enliven the prospect from the windows of the houses.”

Following on from the Criries was Michael Bentley and from 1812 until 1820, John Powell was the last resident to live at the property whilst it was still used as a house. The house was subsequently advertised to let and it contained; dining, drawing and breakfast rooms, eight bedrooms, kitchen, scullery, servants hall, butler’s pantry, and brewing, wine and beer cellars. In addition there was also a coach house, a stable for four horses and two cottages (all detached from the house).

John Gregory’s Upholstery Rooms

The house was occupied by John Gregory, a well-established cabinet-maker and upholsterer in Manchester. He used the property as his new “ware rooms”, where he could display his Brussels and Kidderminster carpets, moreen (a fabric used for curtains) and London paper hangings (wallpapers).

Business took a downturn for Gregory in 1827 and in that year he auctioned off his stock of rose-wood, zebra, mahogany and oak furniture, pier and chimney glasses, Grecian lamps, French screens, library chairs, bath chairs, Grecian couches and sofas, circular, card and other tables, mahogany beds, four-post beds, French beds, tent beds alongside the appropriate bedding and hangings. This list gives us a clear idea of what wealthy residents of Manchester would have been purchasing for their homes and fortunately for John Gregory his business seems to have picked up and he stayed at the property until 1835.

Between 1832 and 1835, Gregory once again decided to sell his stock and the premises were eventually available to let (as was Gregory’s house located at 75 Piccadilly). At the rear of the premises the gardens and stables belonging to the house had been swept away and replaced with a large warehouse, extending from the rear of the property.

The Mid-Nineteenth Century

By 1843, 47 Piccadilly was being used as a warehouse by Messers. Lawrence and Hall, linen and cotton manufacturers. In the 1850s the building was subdivided into offices, a Richard Henry Lightfoot occupied three rooms and Robert Roberts had one room. The change in use of the building was reflective of a change in the Piccadilly area of Manchester itself during this period.

In the 1820s, Market Street was cleared of its medieval buildings, widened and replaced with neo-classical buildings. This in turn created a distinct commercial core of Manchester. In 1842 Manchester Piccadilly train station opened (originally named Store Street Station, then Manchester London Road Station). The station was reached from Market Street via Piccadilly, which opened up the area in front of 47 Piccadilly as a thoroughfare for traffic. By the mid-1850s, the majority of Manchester’s middle-class residents had left the city centre for the suburbs. The Infirmary Lake, an attractive feature just half a century earlier was described as: ” a mere receptacle for the bodies of dead dogs and cats, and other animal matters, in a state of composition.” By 1857 it had been filled in and paved over, becoming the Infirmary Esplanade. This was one of the first markers for the future of this site, as it became a popular public space, more so after the closure of the Lunatic Asylum and Public Baths in the 1840s.

The Midland Railway Co.

In the early 1880s the building was used as a warehouse for the Hopwood & Co. shoe manufacturers. It was still later used by several businesses as warehouses, for example in 1898 it was occupied by both the Midland Railway Company and by Booke, Bond and Co. tea merchants. It’s likely the Railway Company operated out of the former house and the tea merchants used the warehouses at the rear.

The Midland Railway Company were based at 47 Piccadilly from at least 1886 and by the early twentieth century they used most of the building as their offices. It was during this time many original features were lost or altered, for example the original eighteenth-century staircase. Tickets and bills could be purchased from the offices for upcoming trips. The railway company continued to occupy the site until the late 1910s/early 1920s.

The Twentieth Century

In 1909 the new Manchester Royal Infirmary was opened on Oxford Road and the former hospital at Piccadilly demolished. The vacant site was used to create Piccadilly Gardens, open green space to be enjoyed by the public at the heart of the industrial city. In the 1920s and early 1930s, a temporary public reference library was erected on the site until Central Library opened in 1934.

47 Piccadilly also went from being one a few surviving Georgian properties from Levers Row, to the only surviving property. It was completely dwarfed by its Victorian and Edwardian neighbours. From 1939 and into the 1940s number 47 Piccadilly was used as Atkinson’s Hairdressing Saloon. In 1943, Millers, a draper and millinery company was also based there.

The building narrowly avoided destruction during the Manchester Blitz raids on 22nd/23rd December 1940. The warehouses on the opposite side of Piccadilly Gardens were destroyed. This sadly caused the deaths of five men on Parker Street; Albert Ashley, Joseph Hopwood, Kenneth Fenton, Ralph Burrows and Thomas Andrew and the deaths of Charles Smith and Thomas Killeen on nearby Mosley Street.

In the 1970s, 47 Piccadilly was used as a betting office, then as office space and finally retail space. The building received a listed building status in 1994. In more recent years it was used as MOP, a hairdressers and as Marhaba, a newsagent. In 2018 plans have been submitted by Trafalgar Leisure Ltd to Manchester City Council to redevelop the site. This includes the construction of a new building on derelict land adjoining 47 Piccadilly and the absorption of the listed building into this new development. The nineteenth century warehouse at the rear of the building will be demolished in the new plans, but it seems the former Georgian house will be preserved and hopefully have more of its original features on show.

This little house has stood the test of time across three centuries; from taking tea in Mr and Mrs Cririe’s drawing room, choosing furniture in Mr Gregory’s ware rooms, collecting train tickets at the Midland’s offices and getting a hair cut at Atkinson’s Hairdressing Saloon, this building has quietly played a part in everyday life for generations of Mancunians. Who knows what the next chapter will bring.

Researched and Written by Thomas McGrath

~

Sources:

- John Harland, A Volume of Court Leet Records of the Manor of Manchester in the Sixteenth Century, (Chetham Society, 1864)

- Joseph Ashton, The Manchester Guide… (1804)

- Manchester Mercury, 1 October 1771, p.3

- Manchester Mercury, 12 June 1821, p.4

- Manchester Mercury, 18 December 1821, p.4

- Manchester Courier, 7 July 1827, p.2

- Manchester Courier, 9 June 1832, p.2

- Manchester Courier, 16 August 1834, p.2

- Manchester Courier, 28 March 1835, p.1

- Manchester Courier, 21 January 1843, p.6

- Manchester Evening News, 13 June 1941, p.10

- http://images.manchester.gov.uk/index.php?session=pass

- https://pa.manchester.gov.uk/online-applications/applicationDetails.do?keyVal=P6CBJJBCKXM00&activeTab=summary

- http://www.findmypast.co.uk

Absolutely fascinating. Could make a fascinating TV documentary.

How long will number 47 still survive? Thank you.

Gay J Oliver

Sent from my iPad FHSC Group Leader and Web Administration FHSC.org.uk tamesidefamilyhistory.co.uk http://www.tamesidehistoryforum.org.uk gayandmike.co.uk ashtongrammar.co.uk https://gayjoliver.tribalpages.com

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really enjoyed reading this. So many different sources, you build a very vivid picture of the building’s varied past. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lot of of what happened at 47 Piccadilly and 47 Back Piccadilly as been missed out of this article I was the owner of the business at Back Piccadilly from 1978, which had been a Ladbrokes Betting shop there offices where on the 2 upper floors.They were my Landlords. In 1978 the front was Brooks employment agency before it change to a News Agents .The hairdressers in the basement at that time was called The Tudor Salon and it change hands a couple of times after before closing down ,

LikeLike

Thank you for filling in the gaps! It’s always lovely to hear from people with a connection to this building.

LikeLike

MOP was run by a couple of friends of mine. It must have been the mid 90s. One of them,Steve Sanderson, later went on to start Oi Polloi clothing store.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What was M0P My business at 47 Back Piccadilly was there for over 35 years Durnbridge Ltd. ( ,The Pen Hospital ) Don’t recognize this company. Jacqueline Mafston

On Mon, Aug 12, 2019, 18:17 If Those Walls Could Talk wrote:

> Eddy Rhead commented: “MOP was run by a couple of friends of mine. It must > have been the mid 90s. One of them,Steve Sanderson, later went on to start > Oi Polloi clothing store.” >

LikeLike

MOP was a hairdressers which occupied the first floor of 47 Piccadilly. I believe it was the last hairdressers to occupy those premises as the signs for the businesses were still visible in the first floor window in late 2018.

LikeLike

During 1966, I had worked for BR as an assistant telecommunications engineer at Victoria Station, and had visited the BR shop at 47 Piccadilly as part of my duties. A photograph, m04716, taken in 1953 by H. Milligan, is included in the Manchester Libraries Archive, from which the name ‘British Railways’ may be clearly seen above the shop front and the building roof-line. This suggests a continuous occupation from the days of the Midland Railway, through the LMS era into BR days when final closure would have occurred, probably late 1960s / early 1970s.

Link to photo: https://images.manchester.gov.uk/web/objects/common/webmedia.php?irn=8709&reftable=ecatalogue&refirn=68484

One further (minor) correction – Piccadilly Station had actually opened in 1840 as the temporary Temporance Street Station, the 1842 opening being of the short extension to to the new Store Street Station.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello John, thank you for the additional information, it is very much appreciated!

LikeLike