Just a few minutes walk north of Manchester city centre is the district known as Strangeways. To the modern day Mancunian, the name Strangeways is synonymous with the prison located there. However, if we were to travel back in time 160 years, we’d find a once-genteel mansion house in a neighbourhood falling into decay. This is the long lost history of Strangeways.

“Green fields and pastures”: The Location of Strangeways Hall

Strangeways was the name of the hall, the area and eventually the prison. They were all named after the (de) Stangeways family, but where was/is Strangeways? The area is located just north of the city centre, if you leave Victoria Station and walk about ten minutes or so up Great Ducie Street, you’ll be in the heart of Strangeways and near the site of the old hall. The 234 foot tall, Gothic-revival ventilation tower of Strangeways Prison is a local landmark of the site.

Strangeways Hall

The exact date of the construction of the hall is unknown, although it does appear on a map dating from 1641. The main impression of Strangeways Hall is from an engraving from 1746 (see below). The Hall was comprised of two different buildings; an older Elizabethan or Jacobean property with the addition of a Palladian-inspired wing dating from the early-eighteenth century. A newspaper report from 1859 reveals the Hall was “several times rebuilt” and the amalgamation of two different architectural styles was the result of a change in ownership in the eighteenth century. The Reynolds family occupied Strangeways Hall from 1713 and no doubt wanted to preserve the historic structure of the older building, perhaps to show the longevity of the area, but at the same time they clearly wanted to imprint their own tastes on the property. As such the elegant, modern addition reflected their wealth and connections to the local gentry.

The land behind Strangeways contained a pleasure garden with large fish pond and in the wider parklands there were two other bodies of water. The grounds were extremely popular with local people, to the extent Astley’s Circus chose the site to hold a performance there in March 1773.

The De Strangeways Family

The de Strangeways family themselves are certainly recorded in antiquity at the site, although the name appears differently over time; ‘Strongways’ in 1306, ‘Strangewayes’ in 1349 and ‘Strangwishe’ in 1473. In the latter part of the sixteenth century, church records at Manchester reveal the surname was also spelt ‘Strangwaies’.

We know from a legal document that a John de Strangways had land by the river Irk in 1459 and by 1478 his son Thomas Strangeways owned the estate. By the early years of the 16th century it had passed on to his son Phillip Strangeways. Philip married Dulcibella and they has a son, Thomas. Both Philip and Thomas Strangeways appear to have enjoyed flexing their control over the tenants of their estate. In 1518 Phillip granted a tenement on land on Millgate. One condition of this tenancy was that Phillip had free access through the tenant’s house and gardens to the river, so he could obtain drinking water and wash his clothes. Later, in 1540, Phillip and Thomas leased some land and a corn mill to a John Webster. Webster later complained that the Strangeways had seized all his corn.

A settlement document from 1544 reveals the extent of the estate; which consisted of twenty-four messuages (houses), twenty burgages (property located within a town), twenty cottages, a water mill, with land, meadow, pasture, wood, moor and heath, and land in Cheetham, Strangeways, Rochdale, Spotland, Oldham, Cheesden, Manchester, Salford, Oldfield, Withington and Ardwick.

Upon Phillip’s death in 1556, he was succeeded by another son, William. William married Eleanor and had a son, Thomas. In 1587 Thomas Strangeways blocked a footpath leading into Walker’s Croft (modern site of Victoria Station) which greatly annoyed his neighbours. He died in 1590 but his son John was too young to inherit, so Strangeways Hall was held by the Earl of Derby as his land boarded those belonging to the Strangeways.

John Strangeways died on 26 December 1600 and left his widow Elizabeth and his son John who was recorded as a minor. By 1609 another son, Thomas Strangeways (b.1588) inherited the estate (his elder brother may have died). Thomas Strangeways was a church warden and interested in helping the poor and his land held the poor house. He was still living in 1646 but had sold his estate some twenty years earlier.

The Hartley Family

The purchaser of the Strangeways estate and Strangeways Hall in 1624 was John Hartley (1609-1655). John’s father Nicholas Hartley and his elder brother Richard were successful woollen merchants in Manchester. John Hartley held the positions of Constable of Manchester and Sheriff of the County of Lancaster. His daughter Ellen inherited the estate whilst still a single woman. In 1662 she married her cousin John Hartley. He was described in 1674 as a man of “contentious and turbulent spirit”. The couple had three sons: John, Richard and Ralph.

The estate was inherited equally John (d.1703) and Ralph (d.1710). Their brother Richard was reported to have died at sea in 1681. Upon the death of Ralph Hartley, the estate passed on to a cousin and then in turn in 1711 to her daughter, Mrs. Catherine Richards. Catherine died in 1713 and left the estate, in trust, to her accounts and business manager, Thomas Reynolds.

Thomas Reynolds then passed the estate and Hall on to his son, Francis Reynolds (d.1773). Francis, like his father, was an astute business man and he was also an MP for Lancaster between 1743-1773. Francis married the Honourable Elizabeth Moreton, the daughter of Matthew Ducie Morton, 1st Lord Ducie and Baron of Moreton. The couple lived at Strangeways Hall and the following children were born there: Mary, Arabella, Thomas (1733-1785) and Francis (1739-1808). In 1721, Francis Reynolds faced the first of several false claims to the estate. In this instance a man named Hartley falsely claimed to be descended from Richard Hartley who had died at sea.

In 1770, upon the death of his maternal uncle, Thomas Reynolds-Moreton inherited the title of Baron of Moreton. He married Margaret Ramsden in 1774 but had no children. After his death in 1785, his younger brother Francis Reynolds-Moreton (above) inherited the title to become 3rd Baron Moreton. Francis served in the Royal Navy and rose to the rank of Captain. He had fought in the Battle of Saintes in 1782. Like his father he was an MP for Lancaster in 1784-’85. He married Mary Provis in 1774 and had two sons; Thomas Reynolds-Moreton (1774-1840) and Augustus John Francis Reynolds-Moreton. In 1791, he was a widower upon his second marriage to Sarah Joddrell.

His son, Thomas Reynolds-Moreton married Lady Frances Herbert (daughter of 1st Earl of Carnarvon) and was created 1st Earl of Ducie in 1837. Therefore, in little over a century the family had risen rapidly through society through a series of successful marriages. They had gone from middle-class merchants to members of the aristocracy. However, what did this mean for Strangeways Hall?

Industrialisation & Expansion

Until the early 19th century, the area around Strangeways was described as being “green fields and pastures” and was considered to be the countryside outside of the town. For that reason it became a desirable location for the wealthier classes to build their homes. The road through Strangeways to Broughton was dotted with the substantial homes of the middle and upper classes.

Simultaneously, the industrial revolution was also encroaching on Strangeways. As early as 1768, Francis Reynolds granted a lease to Robert Norton with the permission to build a house and silk dying works on the edge of the fish pond for the twice yearly rent of £1/11s/3d (about £187 in modern terms). By 1794 there were two printing works, three dyeworks, a brewery and a bowling green all located on Strangeways land. The smaller fish pond was also used for clay excavations and a small brick kiln was established there. By 1850 this had flourished into a “fancy brick manufactory” and was located just behind the hall.

In 1816 the Reynolds-Moreton family, who had not lived at Strangeways Hall for some decades at this point, appointed William Johnson as estate agent and land surveyor. Baron Ducie had high expectations for the development on his land. He envisioned elegant, symmetrical properties with iron railings, which would appeal to wealthy merchants. The partnership with Johnson proved to be a success and by 1823 a new gridwork of streets and residential housing had been laid out in Strangeways. Francis, Catherine, Julia, Augustus, Great Ducie and Moreton Streets were among those named in honour of the family. Nightengale and Briddon Streets were named after those who had purchased leases and of course, Agent Street and Johnson Street were named after Johnson himself.

The houses did attract the right sort of people, Friedrich Engels resided in comfort on Great Ducie Street when he visited Manchester to write about the urban poor. A row of large houses that stood on the corner of Southall Street was home to a merchant named Mr Crook in the 1840s. According to the memoirs of Louis Hayes: “ [Crook] was very proud of his tall, handsome wife, who stood head and shoulder above him, and was a well known and attractive figure at that time on the road.”

The biggest change to the Strangeways estate occurred in 1838 when Baron Ducie sold land near Hunts Bank and Walker’s Croft to the Manchester and Leeds Railway Company, where Victoria Station was later constructed. The railway had already existed in Manchester for a number of years at Liverpool Road, but this new railway line linked more towns and cities of the North West. The railway cut through the site of the workhouse, which the family had donated land to in 1800. The railway and the station eventually took over the whole site including the paupers burial grounds. Human remains were discovered as recently as 2013 during construction work at the station.

To Let: Strangeways Hall

From the late 1770s Strangeways Hall itself was let to a series of tenants, which reflects the expansion of urbanised Manchester and a substantial change in the role and involvement of local gentry and estate owners. Arranged marriages, inherited wealth and improved transportation from the eighteenth century meant landowners were no longer tied to one house or one location as their ancestors had been. This appears to have been a common trend in the North, even on smaller estates as seen with the Durie family at Damhouse in Astley and the Lilford family at Atherton Hall.

The earliest tenant I have been able to trace is Hugh Oldham, recorded there in 1777. Following him was the Grieves Family. On Christmas Eve 1787 at the Collegiate Church (now Manchester Cathedral) Margaret Grieves married Thomas Taylor, an attorney-at-law. Margaret, or Mrs. Taylor as she was known was a fascinating lady. She ran a boarding school for girls from her home at Strangeways Hall, to educate the wealthier young ladies in literature etc. Upon her marriage, society would have expected her to cease her teaching, as being a wife would be her full time role. However, this was not an option for Margaret and five months after she married she printed a notice in the local newspaper Manchester Mercury to dispel local gossip and announce her continuation of the school (see below). The school was doing so well that in 1789 she hired an additional teacher, Miss Hurd.

In 1792 Margaret wrote her own book, An Easy Introduction to General Knowledge and Polite Literature (For use of the Young Ladies at Strangeways Hall, Manchester). The book cost two shillings (about £11 in modern terms) and was available to be printed Manchester, Liverpool and London. This was an amazing achievement; as a woman in eighteenth-century Britain Margaret had no rights but she stood defiant against the social norms of the time and was a proud educator and author.

The Taylors left Strangeways Hall in 1793 and advertisement revealed the Hall had only 6 years remaining on a 21 year lease. It was described as “Mansion House, called Strangeways Hall, with its extensive offices, double coach house, stables, gardens and fish ponds completely stocked. Together with about three acres of shrubbery and pleasure grounds and the capacious pew or seat in the Collegiate Church of Manchester.” Mr. John Varley and his family took up residency there for the rest of the 1790s. John Varley was a keen gardener and occasionally his name appeared in the press among the prize winners at various competitions.

Following the Varley family at Strangeways Hall was Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Hanson (1774-1811). Joseph Hanson had an illustrious career and was presented at Court to George III. He was also presented with a sword, pike and pistols by his regiment in Manchester. Hanson had previously been engaged to a daughter of John Varley but it was broken off, supposedly because he was arrested in 1804 for attempting to fight a dual with Colonel John Leigh Phillips on Kersal Moor. Hanson used the park at the rear of Strangeways Hall for the training of his rifle corps; one sad incident occurred in 1805 with two cousins named Faulkner and one cousin accidentally fatally shot the other.

Hanson was popularly nicknamed “The Weavers’ Friend” as he was an early supporter of employment and wage reform and he regularly attended and spoke a weavers protests. Somewhat ironically, he rode around in a carriage embellished with two silver shuttles. He became so intertwined with working-class politics that he was eventually imprisoned for six months around 1809 for indicting conspiracy. Upon his release he was presented with a gold cup at Strangeways Hall; amazingly some 32,000 people had subscribed a penny each towards the gift. Sadly, Hanson’s imprisonment took a toll on his health and he died less than two years after his release aged 37.

By the 1820s Strangeways Hall had been let to tenants for some forty or so years and during this decade the Hall appears to have been split into two properties, the older Elizabethan/Jacobean mansion and the much larger and grander 18th century mansion. The older part of the property was sometimes referred to as “Strangeways Cottage” but this should not be confused with Strangeways House, which was a separate domestic building on the land. In 1824 both Joseph Smith, a cotton merchant (and former dissenting teacher) and Mrs Sattlewalth were recorded at the properties. In June 1828 Mrs Sattlewalth of “the old part of Strangeways Hall” had an auction of furniture, feather beds, pier glasses, staircarpets etc.

Later, John Lloyd, his wife Maria (b.1790) and daughter Maria (b.1821) lived in the older part of the Hall. In 1834, five men laying claim to the Strangeways estate rushed into the home of Mr. Lloyd, demanded possession of it and started to make an inventory of the furniture. With the assistance of a neighbour and his solicitor, Mr. Lloyd was able to get the men to leave. Although living in the smaller part of the Hall, the Lloyd family still had ample room to employ two domestic servants.

The Smith family continued to occupy the larger eighteenth century wing of Strangeways Hall. In 1841 only two brothers,Horatio Smith (1811-1855) and Junius Smith (1805-1867) were still in residence. Like their father, they were successful cotton merchants. Both brothers were involved with the Bank of Manchester and Junius was a Commissioner for the police. In 1834 the former prime minister of Mexico was entertained as a guest at Strangeways Hall. The 1841 census also recorded three servants at the property; Hannah Rogerson, Amy Carr and Caesar Augustus.

Decline and Demolition

By the 1850s the once genteel, middle-class suburb of Strangeways was in decline. In his memoirs of that era, Louis M. Hayes recalled the once abundant pond, which had been popular with swimmers and ice skaters was devoid of any fish and was a “dirty piece of stagnant water, a receptacle for dead dogs, cats, boots and shoes, and stray garbage of all kinds”. One night an elderly lady who was well-known in the locality as she had been a muffin-crier (muffin seller) for over 50 years fell and slipped into the pond. Her corpse was only discovered the following day.

The Smith family left Strangeways Hall and the local gentry and middle class merchants followed them. There were far nicer, modern suburbs such as Broughton, Alderley Edge and Didsbury to reside in by this time. Many of their former homes in Strangeways were demolished to make way for industrial works or cheaper housing. The former home of Mr. Crook and his attractive wife, on the corner of Southall Street was turned into a public house. The facades of the properties were completely removed and the interiors remodelled to form The Woolsack Hotel.

Strangeways became a popular area for Manchester’s Jewish residents to reside in. There was an increased number of Jewish immigrants there, who had fled from pogroms and persecution in the Russian Empire. Louis M. Hayes, writing in 1905, blamed the decline of the area on its Jewish population. He even wryly notes “Jews who live in the Strangeways colony have greatly improved both physically and otherwise to what they were even a few years back”. Although Hayes’ comments about the Jewish population of Strangeways can be seen as xenophobic or even anti-Semitic today, they were unfortunately a common narrative in the 19th century.

By January 1858 Strangeways Hall was unoccupied and Thomas C. Moreton, the owner, made the decision to sell the furnishings and demolish the historic property. Manchester Corporation had already earmarked the site for the construction of a new prison and assizes courthouse.

A sale of furnishings gives us a good idea how the interior of Strangeways Hall looked and also the immense size of the property, for example one pier glass (a mirror) was 10ft high and 4ft wide (3m x 1.2m) and a double winged mahogany bookcase was 8ft 4in high and 7ft wide (2.5m x 2.1m). Also for sale were: several mahogany dining room tables, six antique oak chairs, an iron safe, a cottage pianoforte, an 8-day clock, 25 busts and figures on pillars, a four poster bed, mattresses of hair, spring and wool, marble topped washstands, a medicine chest and contents, a huge collection of historic books including ‘Loci Communes Theologici’ dating from 1583, 84 years worth of The Gentleman Magazine, 28 oil paintings and engravings including a Rembrandt.

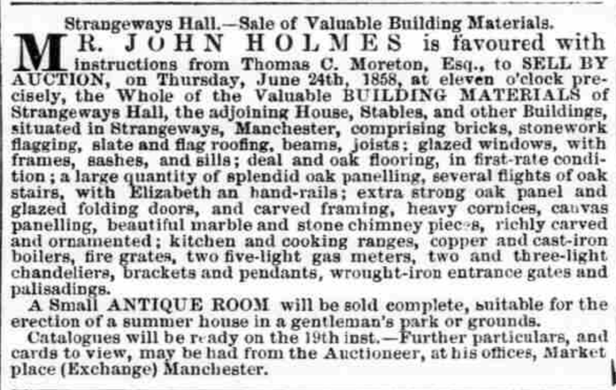

Once all the furnishing had been sold, Strangeways Hall itself was stripped of all internal features including an Elizabethan handrail from a staircase, oak panelling and doors, marble fireplaces, cornices, kitchen ranges, chandeliers and even bricks, stone flags and wooden beams (see newspaper clipping above). An interesting feature of the sale was the survival of a completely intact ‘antique’ room, which was sold and shipped off to an unknown location. Rev. J. E. Segwick purchased so many bricks, slate and timber from the Hall that he was able to build a Sunday School. The impressive entrance gates to Strangeways Hall were installed at the entrance to Peel Park in Salford, where they remained until the 1930s. During the demolition of the hall, a labourer named John Holmes was killed when a stone weighing a quarter of a ton fell on him. Within a matter of months the centuries old Strangeways Hall was completely torn apart and sold, ending the manorial connection to that site which had existed since the 1300s.

A New Dawn: The Assizes Courts & Strangeways Prison

The demolition of Strangeways Hall allowed for the construction of the magnificent Venetian-Gothic style Assizes courts, designed by Alfred Waterhouse and completed in 1864. Until 1877 they held the title as the tallest building in the city. In 1866 Louis M. Hayes attended the Social Science Congress at the Assizes Courts. Lord Brougham was speaking, as soon as he started his false teeth fell out! He quickly popped them back in and said “Ladies and gentlemen our teeth are a trouble to us from the time we are born to the time of our death” and carried on with his talk.

The Courts were regarded as one of Manchester’s finest buildings, the main criminal and civil courts could hold around 800 people. However, during the Manchester Blitz in December 1940 and further bombing in 1941, the courts were completely destroyed. The facade on Great Ducie Street was left standing until it was demolished in 1957. Today the site of the courts and of Strangeways Hall before it is a car park.

Strangeways Prison, built on the site of the ponds in the grounds of the Hall, is what most people associate Strangeways with today. Like the courthouse it was designed by Alfred Waterhouse (with Joshua Jebb) and was opened in 1868, when the New Bailey Prison in Salford (next to Salford Central Station) closed.

The Grade II listed building is an impressive structure and can hold over 1000 prisoners, although it has been a male-only prison since 1963. Following riots in 1990, parts of the prison were rebuilt and its name officially changed to H.M. Prison Manchester.

Strangeways Hall has long since been demolished and subsequently become a forgotten part of history, the former residents not even a memory. However, at least the name lives on in the surrounding area as a little reminder of Manchester’s illustrious history.

Researched and Written by Thomas McGrath

~

Sources:

- Louis M Hayes, “Reminiscences of Manchester from the year 1840”, (Manchester: Sherratt & Hughes, 1905) pp.98-102

- Mrs George Linnaeus Banks, “The Manchester Man” (Manchester: Abel Heywood & Son, 1896) p.380

- Richard Wright Procter, “Memorials of Manchester Streets”, (Manchester: Thomas Sutcliffe, 1874) pp.18-23

- John R. Kellett, “The Impact of Railways on Victorian Cities”, (London: Routledge, 2014) p.153

- http://gent.org.uk/strangeways/thesis1.htm – Contains a lot of detail about the development of Strangeways as an area over history.

- http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol4/pp259-262#fnn18 -History of Strangeways family

- http://thepeerage.com/p2288.htm#i22874 – History of Reynolds family

- http://www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk/online/content/ducie1763.htm – History of Reynolds family

- http://www.mancuniensis.info/Chronology/Chronology1834FPX.htm -Diary of old events in Manchester

- http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/ec185845-61c9-485c-a93f-860aa9512da7 -workhouse records in the archives

- http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/grave-undertaking-manchesters-victoria-station-2573159 – Bodies under Victoria Station

- http://library.chethams.com/blog/fashionable-amusements/ – poster advertising Astley’s show at Strangeways

- http://www.manchesterconfidential.co.uk/best-of-manchester/best-of-mcrthe-lost-buildings – Information on Assizes Court

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/manchester/hi/people_and_places/history/newsid_8234000/8234329.stm – photo of bomb damaged courts

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Reynolds-Moreton,_3rd_Baron_Ducie – Biographical details

- http://www.findmypast.co.uk

- http://www.lan-opc.org.uk/

- https://www.measuringworth.com/m/calculators/ukcompare/

- http://images.manchester.gov.uk/index.php?session=pass

- http://manchester.publicprofiler.org/beta/

- Manchester Mercury, 14 January 1777, p.1

- Kentish Gazette, 4 January 1788, p.3

- Manchester Mercury, 13 May 1788, p.3

- Manchester Mercury, 8 September 1789, p.1

- Manchester Mercury, 7 August 1792, p.4

- Manchester Mercury, 12 March 1793, p.2

- Manchester Mercury, 28 December 1802, p.4

- Leeds Mercury, 4 June 1814, p.3

- Manchester Mercury, 10 June 1828, p.1

- Globe, 18 November 1834, p.1

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 3 March 1849, p.8

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 2nd January 1858, p.12

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 6 February 1858, p.12

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 13 February 1858, p.12

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 19 June 1858, p.12

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 10 July 1858, p.9

- The Ashton Weekly Reporter, and the Staylbridge and Duckenfield Chronicle, 30 July 1859, p4

- Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 21 October 1868, p.7

Hello Tom,

Thanks so much for your research and story about Strangeways Hall. I am a 2nd great granddaugther of Cesar Augustus, male servant to Horatio and Junius Smith (tenants of Strangeways c.1841) and information on the Smith family in general. You may like to know that I have just found an application for Cesar Augustus to marry Charlotte Roberts his first wife in 1847 in Liverpool which states that “the applicant [Cesar Augustus] is a negro with no further name”. I have also discovered that my father (his great grandson) myself and my son have West African dna which confirms the notation to some extent. It also makes me think that he could have been a slave or descended from slave parents. He eventually came to Australia where he named his first house “Strangeway”.

Kind regards Narelle

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Narelle,

Thank you for commenting this is fantastic I never thought this post would be read by a descendent of someone who lived at Strangeways Hall! I had wondered about the origins of your great-great grandfather as Cesar Augustus is quite an exotic and grand name, especially for someone who was in service in Manchester – I’ll have to update the post with the new information. It’s so lovely to hear that he named his new home after Strangeway’s, he must have had fond memories of the house and area.

Thank you again for commenting it’s always lovely to hear feedback!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Tom. I also have a basic tree of the Smith family if you ever need it. I am on holidays but will be able access the info in a few weeks.

Cheers

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Thomas, I have just found an application to marry in Liverpool for Cesar Augustus and his bride to be Charlotte Roberts in 1847. The document is quite standard but a notation at the bottom of the document states ” The applicant [Cesar Augustus] is a Negro and has no further name”. As you suggested his name is quite exotic and it now appears that he may have been a slave. I have not progressed any further in confirming this but a DNA test done by a number of our family confirm varying percentages of West African in every participant. If Cesar’s statement that he was born in Brazil are true then it is plausible that he and maybe one or both of his parents were part of the slave trade between West Africa and Brazil in the early 1800’s.

Cheers Narelle

LikeLike

Hi, this is a wonderfully researched piece, Tom. Thank you!

My name is Heather Ruth Strangeways, only daughter of Thomas William, now deceased, formerly of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Derby. Although the lineage is tangled, I am fairly certain that my ancestors built the original manor house before migrating to Northallerton (my line ended up living at Cheswick near Holy Island by the 16th century).

My interest in all forms of history became severely stilted when I reached secondary school but my dad’s death at eighty, in 2014 nudged me towards further family research. I had visited the local history section at Manchester Library in the late 1980’s hence I knew that there was a medieval family home on what is now the prison.

I’ve read some fascinating snippets of information on the Strangeways of Salford. At one point, several Strangeways brothers murdered a member of the Gresley/Greeley family, another notable medieval Manchester family.

I’m wondering what sparked your interest?

Fantastic article anyhow and very much appreciated!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Heather,

Thank you so much for commenting. How interesting it would be if you were related to the Strangeways family of the Hall!

My own interest into the Hall was sparked by curiosity really, I’d heard it mentioned in histories but couldn’t really find out much more – so hopefully I’ve added to that!

LikeLike

Hi Tom, What a fascinating, well researched article.

My name is Heather Ruth Strangeways, only daughter of the late Thoma William, of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, later Derby.

On visiting the local history section at Manchester’s central library in the late 1980’s, I discovered that the site of what is now the infamous prison was at one time a medieval family home.

When my dad died in 2014, it spurred me towards further research into the enigmatic Strangeways family, being the last to carry the surname in my lineage.

Although tracing a direct ancestral line is an almost impossibly convoluted tangle, I am certain that my ancestors built the original medieval Strangeways Manor before migrating to Northallerton. My branch ended up near the Scottish Borders by the 16th century. Several Strangeways are buried on Holy Island and, it turns out, at Manchester Cathedral.

I’ve found some marvellous snippets of information regarding the Strangeways of Salford. In one incident, several Strangeways brothers murdered one of the Gresley/Greeley men (I think it was a question of defending their sister’s honor!).

Thank you so much. I enjoyed your article immensely as part of my continuing research. Medieval Manchester now has me in it’s mesmerizing grip!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A considerable piece of work Thomas – thanks you for you time and effort. Would it be possible to quote a small piece of text, with appropriate acknowledgement and link back to the original post, for a broader based study of the Strangeways/Cheetwood area I am working on. My post is largely concerned with recording the more recent developments photographically, and it would be useful to provide a more informed background history such as your exemplary work. Many thanks Steve.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Steve, thank you for your feedback! I would be more than happy for you to quote my work, as you mentioned. I’m glad it is of some use to you. Tom

LikeLike

Thanks ever so Thomas, it really has been most helpful. Will be posting the first of a number of pieces on Strangeways soon, having photographed the area for some 10 years now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s my appreciation of the areas Modernist architecture https://modernmooch.com/2018/02/05/strangeways-manchester-1/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was delighted to find this article, and to see how much has become available since I wrote my MA dissertation at Leicester back in 1973. Thank you too for the courtesy of a reference. I immensely enjoyed reading this blog. So much has changed since I was exploring Strangeways back in 1973 – I enjoyed a tour round the Boddington’s Brewery back then. I shall try to update some of my material and make it available. I stopped in 1868 but Strangeways deserved a continuation. Because of that work I became fascinated by Louis Golding and his writings. I have just discovered the film of Mr Emmanuel, based on his book, is available to watch online.

Congratulations and best wishes, Frank Gent

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Frank,

Thank you for your kind comments! I really enjoyed and appreciate your work and I’m very grateful you decided to make it available. I’m glad to hear Strangeways continues to be an inspiration for you!

LikeLike

Thank you so much Tom for your amazing research which may well help me to solve a 60 year family mystery! My father always told me that our family had once owned the land on which Strangeways prison was built and I have to admit I had rather dismissed the idea. After having researched my family tree for over forty years and finding no possible links I was amazed when I stumbled across your article and realised my grandmother’s great grandmother was a Hartley. Her father i.e. my 4xG grandfather was John Hartley, gent of Ardwick. He was born in 1769 the son of George Hartley and Ann Chetham.

I do not think he was a direct descendant of the John Hartley who purchased the estate from the Strangeway family but I have a copy of John’s father, Nicholas Hartley’s will from 1609 in which he names 5 sons who outlived him, Richard (his heir), John (who purchased Strangeways), Nicholas, Thomas, George and 2 daughters Margaret and Elizabeth as well as his wife Ellen who inherited a third of Nicholas’s land and properties. There are records of 5 other children who pre-deceased him.

John, as the second son must have been born around 1600 and not 1609 as widely recorded. I hope to find I am descended from one of his brothers which would explain my family story. Either that or my John is descended from one of the unsuccessful claimants to the estate!

May I please include a link to your article on my tree on Ancestry and My Heritage?

Best regards

Barbara Boardman

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Barbara,

Thank you for your comment, I’m glad it’s helped put a few more pieces of the puzzle together for your family mystery! I’d be happy for you to share the link on your family trees!

LikeLike